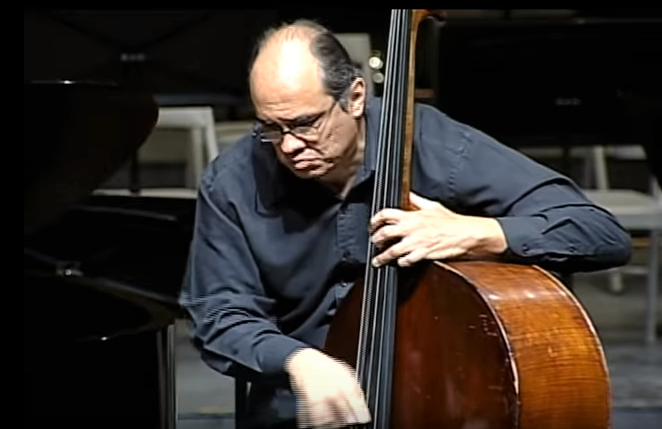

One of the most recognized Mexican jazz players. He has taught music through decades and he is known as a great double bass musician and as the creator of LaFaro Jazz Institute, a place where young people get in touch with their own feeling through the music. Agustín told me his story…

Mexico City, 2018

-How does your career start in jazz?

-In jazz specifically… I was a rock and funk musician; everything about 60’s and 70’s music. I played the bass in a band. One day in TV I watched the Newport Jazz Festival, which was weird to be seen on the screen those days. I saw a double bass player and it got me. I started to ask myself what was that instrument, what was jazz. A door opened up to me. After that, Jorge Saldaña, an important Mexican journalist, presented some jazz bands in his TV program. He presented Sacbé, the band of Eugenio Toussaint; and Blue Note, the band of Roberto Aymes. Aymes played the double bass and it got my attention.

I saw them play in a place named “La casa de la nostalgia”. A friend and I went there, we were rockers but we started to like jazz. We met Roberto there. Also, there was Alejandro Corona, the piano player. That was when we got connected. I started to search for a double bass, Roberto helped me and he gave me lessons of solfegio.

I was still in highschool. I started thinking in the possibility of dedicate myself totally to music. Since I was a kid of average family in Mexico I thought that music was a hobbie, but when I spoke to Aymes, Corona and everyone, they told me: “no, we are completely dedicated to this”. I even thought: “I am saved”, because I didn’t know what to do with my life.

-How does a person learn jazz when he is part of a different culture. At those days jazz barely appeared on the mass media in Mexico.

-It is complex because you don’t even know where to start. Roberto used to invite us to his house and he put on records of Charlie Parker, Bill Evans, European jazz… I started by listening, by trying to get familiar with the language. I started to go to jazz concerts, there was just a few in Mexico. The Blue Note that was disappearing back at the time presented another trio: Corona, Aymes and a drums player: Lalo Sánchez Cárdenas. I was their groupie. That is how I learned, beginning from no place, no internet, no YouTube. Those things could have helped a lot, but no… I only had the records and the reunions of jazz players.

-I have my own idea about the history of jazz in our country, which I built based on many stories of different musicians. What is your story?

-In 1977, 78, I started to feel interest about jazz. There was no much jazz in Mexico. European bands used to come, thanks to the Germany’s Goethe Institut. There were festivals where I used to go. I saw Bill Evans with Eddie Gomez and Elliot Zigmund, incredible. I saw Mingus.

Aymes was my guide. Sacbé stopped playing at the time. The bands of older people, like Chilo Morán, were not active anymore.

I got a double bass. Aymes gave me lessons. He told me once: “hey, there is this girl who just came here, she’s not doing jazz but she needs a double bazz player”. I didn’t play a thing, but he said: “go for it! Who cares?”. Ok… who is she? She was Betsy Pecanins. Me and my friend Fernando went to see her. We built a pop and blues repertoire. After that experience, Olivia Revueltas, a pianist, invited me to play with her. Just imagine, she is the daughter of José Revueltas and the niece of Silvestre Revueltas. She played at a place named “El Chato”, a small bar over a restaurant in the Colonia Roma. That’s when I started playing jazz, with Olivia. Very poorly, I didn’t know a thing, the Real Book didn’t even exist; at the time you had to learn the songs by ear, follow Olivia however you could… it was a chaos.

-I remember you also had an interesting experience: the opportunity of going to New York.

-There was an important cycle of concerts in the Teatro de la Ciudad. Dexter Gordon came by. I was with Aymes and we decided to go because Refus Reid was coming, a double bass player; I had his method because my father bought it in the United States for me. It was a book that helped me starting to learn how to play jazz. I told Rufus: “I am a Mexican double bass player and I want to learn jazz, is there any possibility that you could teach me a small lesson?”. He answered “tomorrow I will be having breakfast at these hotel in these zone… go and we’ll talk”. So I went, I had breakfast with Rufus, he was supposed to send me a letter after that; in those days the letters used to take months to arrive. “Hey… I can teach you in the summer of 1981”. I said: “Ok… but, Where would I stay?”. “In my house -he said- because at the suburb where I live there are no hotels”. I went to study with him for a couple of weeks. The whole horizon opened up for me.

The day I arrived he said: “we are going to New York so you can hear jazz”. He was living in New Jersey. Rufus, as he was known for all the owners, was able to get in any place, and I was going after him. I met big musicians -Ron Carter-, he introduced me to everyone as his student from Mexico. That opened my perspective about what jazz was. You go to New York and see everything about it.

In Mexico there was people who used to tell me “change to the electric bass… the double bass for what? It is difficult to amplify, difficult to take, difficult to play”. After going to New York I realized that the double bass was alive.

-How did you formalize your learning of jazz?

-With discipline. Rufus gave me a work routine, he told me what to do. I brought with me the Real Book. He told me to transcribe some things from the records. It took a lot of work, I didn’t have ear preparation. I never went to a school of music, I learned by myself. I only had one teacher of classic double bass.

-Did that influence the decision of creating a jazz school?

-That happened many years after. I wanted to create that school thinking about the place of learning that I would have wanted at that time. It would have been important for me that a jazz school existed in Mexico when I was starting to learn. That’s how LaFaro Jazz Institute was born.

-Is there a particular methodology in LaFaro? Are you using a method taken from another jazz school? How does it work?

-I’ve taught particular classes for many years. People started asking me for double bass classes since I was very young, in my twenties. I started to research about the educational part of jazz and double bass. After all that time I found the opportunity to found LaFaro.

Much of what we are looking for in LaFaro is the old school, it means that it is not as much as an strict methodology, it is about living what jazz is. You have to transcribe from the records, listen, sing, get together with the other jazz musicians you admire, help them to carry their amplifiers, go to the concerts. We do have improvisation courses, auditory training courses, but we insist in the fact that people like Charlie Parker didn’t go to school, Dexter Gordon didn’t go to school… John Coltrane… none of them did. How did they do it? They went inside themselves and found things of themselves to create their own language.

-I have this idea coming in and out of my head. I see people with lots of talent, some of them study, some others do not, but there is always the main subject: the money. The lack of money in Mexico as an impediment. But I think: many of the greatest jazz players come from the US, from the times of segregation… they didn’t have much money either and they had to deal with racism, but they were still creating and studying… What do you think?

-The one who is going to make it, is going to make it at any cost. I have seen people with lost of talent in LaFaro and I don’t say much to them… I just say “go on, transcribe, come and play”, and they do it. There is no much to say. The less you talk while you are teaching jazz, the better, because they alone know how to walk, they know what to do. LaFaro is more like a place where they come to play, to get to know more musicians. I don’t believe in the concept of the strict jazz school, because jazz is not like that. The alumni has to take the responsibility, if they have the talent and the joy for playing, they are going to make it; if they don’t, they just fail… those guys who think that jazz is like a fashion, they don’t last a month, they leave. The absortion of a language is created by listening… so if they don’t listen they won’t be able to speak that language. They want formulas, but there are non. Jazz is complex.

-You have to be obsessed…

-That’s precisely what I was saying hours ago to an ensemble. It has to be an obsession: you keep thinking in this piece, in the solo… you are getting inside it, you search for, it is something that rips you up inside. The same would have to happen with classic music or funk, if you are into that music, you have to feel it all the way.

-Tell us some stories about the people who taught you jazz… and your students. Because this is a process of learning and transmitting…

-Of course. There have been many musicians, most of all from the old school. One in particular, who took me as his student, was José Sánchez, people used to call him “El Tigre”, a great Mexican drums player of jazz. You couldn’t say that he figures in the story of jazz as much as Chilo Morán… however, I think he is very important. I started playing with him and he started to tell me how to play double bass with drums, how to get together to create swing.

He used to tell me many stories, he came from Tijuana. He have had been in Los Angeles, San Diego; he had met many of the greatest musicians in the jazz history from the 50’s, 60’s… that was inspiring for me. He used to tell me “this bass player, Joe Mondragón, I played with him once, he made a wonderful solo… after that everybody went to get heroin”. He said he didn’t do heroin, bue he was very close to it because Joe Mondragon was like “look… when you get heroin a whole new world of possibilities opens up for you”. At the end he decided not to try it.

If you think about it, Bill Evans used to do heroin and he was wonderful. Charlie Parker did heroin and he was a genious. I actually doubted if heroin pushed them or gave them all their creative part. Fortunately, I have never done heroin, I am too conservative for that. But those doubts stay in mind.

I’ve been able to play with great musicians: Chilo Morán, Héctor Infanzón, Tony Cárdenas (RIP), in the Arcano, a place in the Centro Histórico de la Ciudad de México. There is Salvador Agüero, “El Rabo”, an old drums player, he is 80 something, he knows about the first jazz place. Young guys who wanted to play, used to go and hear us. They used to tell us: “you are so tender… you don’t realice that jazz in Mexico is very difficult”.

Now we are in a great era for jazz in Mexico. There are many jazz bands, schools, Youtube, social media… We didn’t have that back in the days.

-Which jazz players in Mexico would you recommend?

-Many. Diego Franco, sax player; Roberto Verástegui, piano player; Héctor Rodríguez, guitar player, I produced his album and played on it; Gabriel Puentes, drum player; Emanuel Chopi Cisneros, piano player… many, Aarón Cruz, Benjamín García. There are plenty of good double bass players in Mexico, young guys. Many of them studied with me and now they found their way. They make it.

-Tell us about how the genres can enrich each other. You have played in popular music projects, but you invest all the deep knowledge you have in those.

-Jazz is difficult to survive in any place of the world. In New York they are almost getting to the point in which musicians have to pay to play… I’m talking about big musicians. This is because the want to play in the clubs to keep themselves in shape. They get money from teaching, from going on tour to Europe and Japan. Playing in New York is for practice, for creating new projects.

What happened to me is that I got to the point when jazz was cool and everything. I lived in a small place. My drum player, he used to play also with Mijares, asked me to help him with the creation of a new band for a new Singer from Guatemala, who was coming to live here in Mexico. I didn’t want to but I took it because I couldn’t take it anymore, I had to live in a better situation. Jazz is great but there is a point when you want to get a car, to have a better standard of living. So we made the band and money started to come. I stayed there for two years because it was too much… but I had the chance to save money.

After that I was invited to play with a Cuban singer. I stayed with him for five years. Everything got better. But I never left jazz, I kept my projects. I had kids at the time. Then I closed that chapter. Sometimes I still record with pop artists, but I’m not in their complete project. Actually there are just a few pop projects actually working now. It is not like the Golden age with Luis Miguel, Juan Gabriel… many jazz players used to work with them.

–Quincy Jones is coming with Qwest TV, the “Netflix of jazz”… maybe something good will happen. If people get to know more about jazz, it will grow stronger.

-Of course! And jazz is going to live forever, whatever happens, because it is a profound and interesting way to create art. It is for few people, it is not for everybody, jazz itself does not allow many people. I hope the musicians study a lot. You see the case of Antonio Sánchez. There are very musicians going to the US to study. I hope they come back to Mexico and work on it.

Mexico is a good place for jazz. It is not very close, it is not very open either, but there is some help. There are many festivals, it is cool. Jazz will always be alive in Mexico.

-Argentina, for example, we can see how tango embodied jazz; in Brasil it happened to bossa nova; it happened also when the European music influenced the US tradition, in the way the grades are treated melodically… Also, in Mexico we used the traditions of the broken chord and the syncopation in triple time… So Do you perceive any distinctive quality of the way Mexicans double bass players play jazz?

-Yes, some people have. Most of all those who have grown with that music. It has to do a lot with, I think, huapango and son. There is this band Sonex, which I think is quite interesting because it is becoming more creative, improvissative, jazzistic, but we always have as our models the black musicians. There are a few cases: most of the double bass players here have another kind of influences: fusion, rock, progressive… most f the bass players come from that.

-Would it be important for Mexico to create an unique sound o do you think we are ok the way we are?

-That has to be done, naturally, I don’t think we have to work on it. The bass players from Chiapas, Veracruz, who have had those roots would have to do it in a natural way. It can not be forced. There we have the case of Enrique Neri, a great Mexican pianist, who incorporated some of this things in a super natural way.

But what I see are guys into the tradition and into the contemporary jazz music. They are not into Mexican music.

-Is there anything that you want to add to this interview?

-Now we are living a great era for jazz in Mexico. Many young people is in it. We have YouTube, social media, those are very helpful for learning. The jazz community has grown a lot. The kids I see in school have the conviction to play. We are in a good moment. I don’t know what is going to happen in Mexico with the elections… but I hope there will be more venues and support for jazz, that would be awesome.