Francisco Téllez created the seed of jazz in Mexico. His school marked the beginning of an enormous tree of musicians and teachers that today are the cornerstone of my country’s artistic life. His case is a strange one because, among many reasons, instead of becoming a big album composer, producer and seller, he decided to educate Mexican musicians and transform musical education. As I told him during our interview: someone had to do the job.

So, here are memories and the vision of El Maestro Téllez, whose name deserves to be engraved in history.

House of Francisco Téllez, Mexico City, 2018

Degenerated Jazz Becomes a Career in Mexico

I was born in 1945, I started by listening records of 1948 my father used to collect, in those there was Art Tatum playing, the great piano man.

When I was studying in the Academy of Music, I had some partners who played blues, jazz. Estaban Antonio Alemán, Enrique Nery, Roberto Martínez Chávez… they used to play classical music and some popular music, but if they did then people at school would take away their pianos. But we always felt the need of playing popular music.

The education reform started since then, in 1968, because that was my objective. Héctor Infanzón (a famous Mexican jazz piano player), who was one of my first students, remembers that when I started the jazz workshops at school, the first concert was played at Cuba 92, in the Silvestre Revueltas auditorium. I played next to Jazzamoart (Mexican painter, whose art is inspired by jazz) and it was a free jazz program. That’s why I created the school: I came from an environment where jazz was prohibited.

First I started teaching classical piano at the Escuela Superior de Música (ESM). Then Francisco Núñez started the idea of the workshops, which was excellent because there was a lot of desertion at music schools: you had 1500 students starting the career, after the first year there were 700. Music careers were very long (10 years), now those are divided. Musicians who actually completed their careers, we were around 5 or 4 o 2. That’s why Núñez created the workshops as new alternatives: music spelling, opera, Mexican music, Antique music and jazz. All of them disappeared because the students and the teachers were not very involved, except for the jazz workshop. We kept going on and on having the need of doing that music, having the need of creation.

Eventually there was a point when Pola Mejía, a pedagogue from the school, told me: “the workshops approach is enough to make a plan career, it only needs a few things…”; then I started to work harder on it.

I created 11 career plans but they were still getting rejected for one thing or another. Those were written with a typewriter, the letter “z” got broken because I wrote the word “jazz” so many times. I appreciate the ideas added to the plan career over the time: I didn’t do it alone, it was created with help of many pedagogues.

To Learn Jazz: To Teach Jazz

When I started writing the career plan I had nothing, there was nothing. Francisco Mondragón, a great guitar player, who is now dead, gave me some career plans, pamphlets and programs from different schools around the world. He studied in Germany, Belgium, in Berklee. That helped me organizing the classes. That’s when I thought that history of jazz should be part of the syllabus, which was my personal proposal.

The ESM curriculum is organized according the evolution of jazz. You study each one of the styles according to their decades. That’s the project. There was a time, a long time ago, when I had the opportunity to take this syllabus to Berklee. They answered that it had a very interesting organization.

At the time there were no jazz schools in Mexico. Now, I find very interesting the fact that many of my students created jazz schools everywhere: Tuxtla, Hermosillo, Ciudad Juárez, Monterrey… They have also created jazz bands. I think that happened because at the ESM we had four band levels, conducted by Enrique Valadez, Antonio Servín, Zósimo Hernández. The students started having the need for playing in a Big Band, that is why we now have the Zinco Big Band, the Big Band Jazz de México. The difficult part is the budget, to obtain the money to sustain 17 or 25 musicians, to get publicity. But this jazz movement keeps growing.

Jazz Festivals

I organized 32 jazz festivals. The point was to introduce the students to the audience. The big question was: I taught them, now… what do I do with them? The idea was to present them in the same scenario with professional bands. That’s how big musicians met the students. Like the Beaujean sisters, they had a show there with the Big Band Jazz de Mexico and then they started collaborating. Israel Cupich, Sylvie Henry also started their careers like that.

Jazz Appears in Mexican Radio for the First Time: 1959

Juan López Moctezuma was a jazz promotor, he used to conduct the radio programs Panorama de Jazz and Jazz en la Cultura of Radio UNAM. Moctezuma at the beginning had to program classical music. He came with a big idea in the New Year’s Eve of 1959: to broadcast jazz, even knowing that he could be fired if he did that. That was the start.

He kept on promoting jazz, organizing great concerts at the Casa de la Paz, which was in the street Merida. Before that there had been other promoters, but I don’t know much about them, I am talking about the one I met. Juan López Moctezuma helped us with our jazz programs.

Juan López Moctezuma was the first one who gave us publicity. After him, Panorama de Jazz was conducted by Germán Palomares, and then by Kazuya Zakai, the painter. Eventually it was taken by Roberto Aymes who is still conducting it.

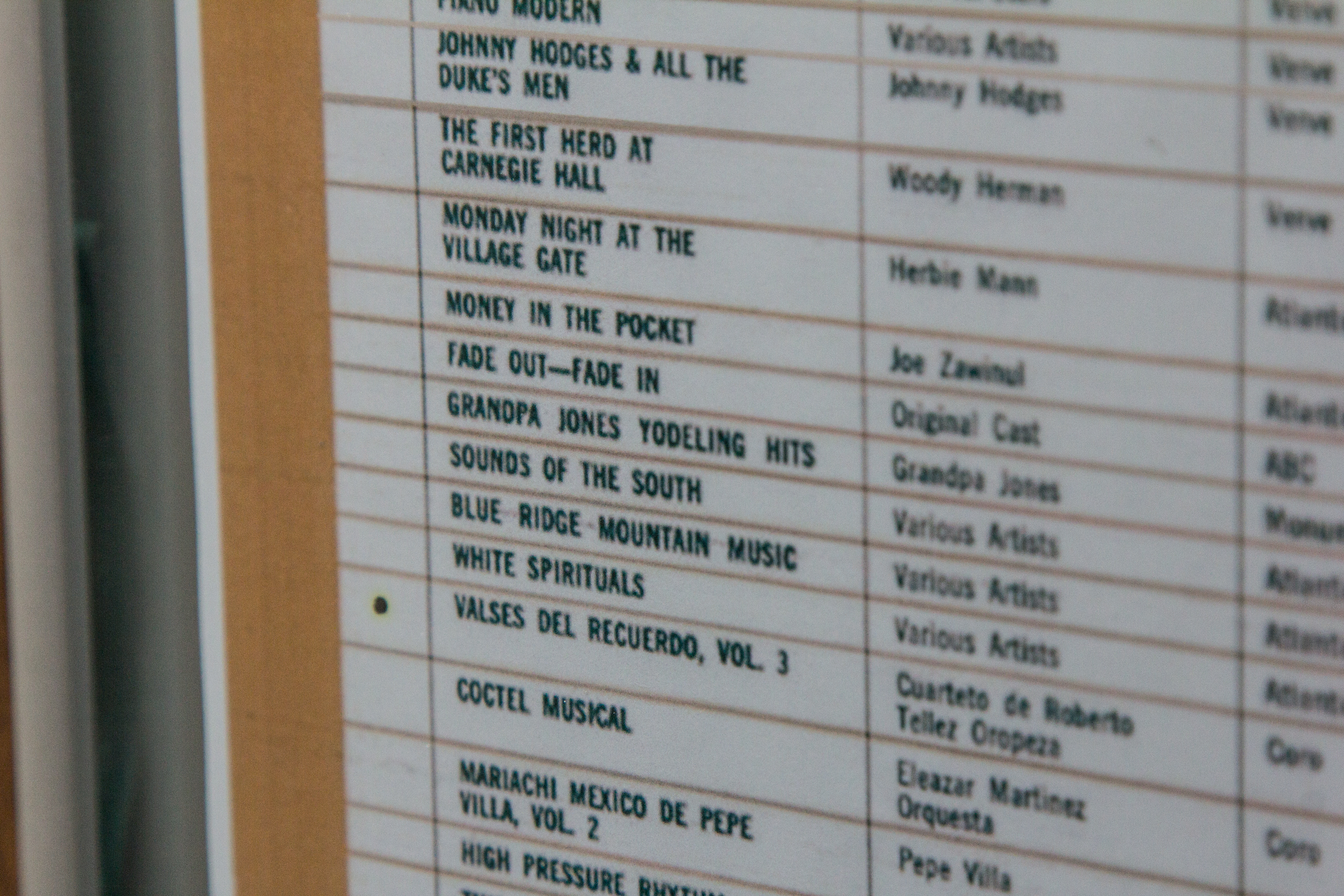

I really consider Juan López Moctezuma because the radio station was next to the Architecture University, you could just get in as if you were in your house, there was no protocol. You could just say hi to Juan. He had a notebook in which he recollected every picture and news about jazz, I copied his strategy during many years, my notebooks were named “El jazz en México” (Alaín Derbez took these as an important source for his book “Jazz en Mexico”). We didn’t have access to any type of information. You can’t believe that back then there were no jazz books, the only thing we had was 17 books at the library Benjamin Franklin. That was it. My botebooks are 7, and everything is there.

The Musical Revolution: From Cabaret to the Classroom and Cafe

We must consider that in Mexico we had a regent, Ernesto Uruchurtu Peralta, who took down the jazz places that existed at the time: El Rigus, La Concha… those were not specifically about jazz, those were more like cabarets. Musicians used to start the night with a jazz theme and then the show started. I worked like that, it was the usual.

When those places closed, it was the beginning of the jazz café. Those were open during the afternoon and they didn’t sell alcohol. At the time we started playing in some high schools. I played at the Prepa 5, at the Medicine School, at the Prepa 1. Juan José Calatayud (Mexican piano player and composer) used to do that too.

There was a global musical revolution: the places were jazz was played were cabarets, but Dave Brubeck started to play Take Five and all that in different schools.

The New Jazz Appears in Mexico Cinema: Jodorowsky

Somehow I must relate all this to Juan López Moctezuma, who saw us playing somewhere and took us to play in Alejandro Jodorowsky’s film Fando y Liz. I play the piano during the first scene, my hair was very short. Alejandro thought it was a novelty to put a piano into flames and start a musical revolution. Someone wrote somewhere that was Henry West the one playing the saxophone in that scene, but that’s not true, it was Armando Pérez Durco, the saxophone player of my band. There was also Jorge Pérez playing the double bass, and Pablo Briseña in the drums.

After that, we taped a TV program with Jodorowsky at the Canal 5. There was Alejandro braking a piano while we were playing Take Five, which was the new jazz at the time. The TV program was taken away from Alejandro because he announced that the next show he was planning to kill a cow in the scenario, and that was too much for the channel. But the show we taped, which was something completely new, was taken to New York for contests and more.

Foxtrot Arrives in Mexico

My father had a band in 1947, I was born in 1945 and I was taken to the rehearsals. My grandfather was the composer of the “Canción mixteca” (José López Alavez), and people say that he was who brought foxtrot to Mexico. He traveled with the band of the police office to the US. Those years Mexico had nothing, not even radio. When my father came back he brought music sheets of foxtrot.

Thank you very much, dear Master Tellez, for opening the doors of your house to Bop Spots and let us be part of the history you started and keep writing.