By: Estefanía Romero

Mick Carlon is bringing the history of jazz to young people. This professor from Centerville, Massachusetts, has writen by now three novels in which idols as Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Lester Young, Ella Fitzgerald and many more, can talk to all of us.

His work, which is now part of the teaching of public schools in the US and many parts of Europe, is distinguished as the result of 30 years of readings, research and interviews, processed within the great intelligence and sensibility of Carlon facing the human tragedy, but also its greatest feelings.

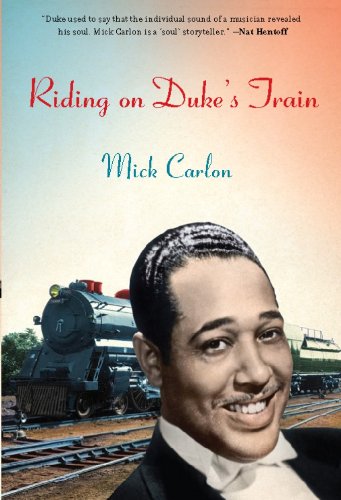

Here, Mick tells his story as the author of Girl Singer, Riding on Duke’s Train y Travels With Louis.

–Dear Mick, your books are for teenagers but I happened to learn lots too. Tell me about this.

-Many, many adults—including Dan Morgenstern and Nat Hentoff—have told me that they enjoyed reading my novels as much as any so-called “adult” books. I made a conscious effort not to “dumb down” the writing. Because these novels are meant for young people ages 12-19, I did not want to wallow in subjects such as heroin needles sticking out of Charlie Parker’s arm—but I also wanted the writing to be clear, direct, and not at all condescending. As a veteran teacher, I know that it is so important to never, ever patronize young people.

– I love how you reflect the personalities of the characters and some of the basic and most important characteristic on playing jazz, like “being yourself, play yourself”. What does all that mean to you?

-My late father loved big band jazz, and I heard it while growing up. Since I was born in 1959, the Beatles and Bob Dylan hit me in a massive way—yet I also always loved my dad’s music. When Duke Ellington died in May 1974, I read a piece by Ralph J. Gleason about Duke in Rolling Stone magazine. Now I knew Gleason from his writings about Bob Dylan—I did not realize that Ralph was a jazz man, too. His piece on Duke opened my eyes more than any other piece of journalism I have ever read. It made me realize that the man I often saw on television, Duke Ellington, was not simply an entertainer—but that he was an artist of the first rank, America’s Bach. After reading that article, I took my dad’s music much more seriously, and that’s when I began reading the great Jazz writers like Nat Hentoff, Dan Morgenstern, Whitney Balliet and, later, Gary Giddins.

So years later, when the idea to write these novels hit me, I had close to 30 years of reading about Jazz and close listening to Jazz floating around inside my head. Plus, one of the many qualities I love about Jazz is that it allows the artist to BE HIMSELF OR HERSELF. The musician is playing his/her experiences on his/her instrument. Jazz is freedom of expression, beauty, and excitement all in one incredibly pliable music. Nat Hentoff naturally said it best: “The more I hear Jazz, the more I want to hear Jazz.”

– Through your readings we can talk with Lester Young, Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie. Did you get some real dialogues from them or other characters?

-While writing these novels, I’d immerse myself in what these musicians sounded like when they were speaking. Thanks to YouTube, interviews with Duke, Louis, Pres (Lester Young), and Dizzy are free and available. So I would listen and listen, trying to capture the cadence of the musicians’ speech. With Lester Young, of course, he created his own universe of language—and that was so much fun to recreate. Pres was as much a linguistic artist as he was a musical artist.

A beautiful guy named Don Manning—he was a drummer and writer from Portland, Oregon who has since passed away–read Riding on Duke’s Train and Travels with Louis and he began phoning me late at night. “I can’t believe someone has written these books!” he’d say. When I told him that Basie and Pres were the subject of my next book, he sent me a recording of Count Basie speaking in Don’s own kitchen! I couldn’t believe Don’s generosity, and I’d listen to that baby again and again to try to capture Basie’s laconic style of speaking. Bill Basie was beautifully laconic on the piano AND when he spoke.

So a great deal of work went into making sure that these artists’ speech patterns were accurate. Of course, with an artist like Ivie Anderson, there are simply no surviving recordings of her speaking voice, so I had to improvise. Nat Hentoff told me that my Ivie in Riding on Duke’s Train brought tears to his eyes “because you thoroughly captured that salty, incredible woman.”

– How deep had to be your research on jazz for you to get to this amazing amount of knowledge? For example, you know things about Louis Armstrong that I never read or watch on a documentary before.

-My research, like I said, was over 30 years of reading about jazz musicians for pleasure, not knowing that one day I’d be writing about them. However, for Riding on Duke’s Train, I had no idea the itinerary of Duke’s spring 1939 European tour, so I relied on John Edward Hasse’s superb Ducal biography for the cities and dates. In my opinion, Dr. Hasse’s Duke biography is by far the best of them all.

However, I did have a secret weapon for Travels With Louis and his name is Jack Bradley, whom I’ve known since 1991. Jack met Louis in the late 1950s and soon became a friend, confidant, and Louis’ favorite photographer. Because Pops trusted Jack so much—he called him “my white son”—Jack’s photos of Louis have an intimacy rarely equaled.

But as I was writing Travels With Louis, I’d ask Jack questions like, “What was Louis like to hang out with?” “What did you two talk about?” and “How did Louis react when bigotry was directed at him?” We know from Louis’ reaction to the Little Rock 9 in 1957 that he would grow incredibly angry when others faced the evil of prejudice. His quotes to a reporter about Governor Orville Faubus using his National Guard to keep the nine black students out of Central High School were filled with righteous anger of Biblical proportions. But I wanted to know how Louis Armstrong reacted when he faced bigotry directed right at him. And Jack told me this story:

In the summer of 1960 or ’61, Jack and Louis were driving in Connecticut to a gig that night in Hartford. Jack was driving and Louis had to use the restroom, so Jack stopped at a gas station. Back then you would ask the manager for a key to the men’s or ladies’ room. So Jack stays behind the wheel while Louis walks off to ask for the key. Remember by the early 60s Louis has been on the cover of Time magazine, he’s met kings and popes and has been famous for over 30 years. In no time Louis is back in the car. “That was sure quick,” said Jack. Louis was silent for several moments before replying, “That cat said that I can’t use his restroom. ‘I know who you are, Armstrong. I even like your music—but I can’t let no colored use my restrooms.’” Jack wanted to leave the car and punch the man in the face, but Louis stopped him, saying, “That will just get you thrown in jail, Jack. Come on, let’s drive on.” Jack drove back on the highway and Louis was quiet for at least five minutes. Then he said: “That cat just doesn’t understand what life is about yet.” You see? Louis Armstrong grew angry when prejudice hit others—but when it hit himself, he was reflective and even generous. What an utterly unique and superior human being Louis Armstrong was!

So information like that really helped me when I was writing Travels With Louis. Jack would tell me other things, too, like how much Louis loved to wear shorts and sandals when he was relaxing at home. I love Jack so much—and he has given me so much—that I decided to name my young character Fred Bradley in his honor.

When I’d written the first draft of the novel, I asked Jack to read it. He’s a salty old cat, brutally honest, and he looked me in the eye and said: “If you’ve written one phony word about Pops, I’ll call you a dirty motherfucker to your face!” And he meant it, too!

So a week later when Jack called me I was understandably nervous. “Well?” I asked. “What did you think?” And Jack said “I understand that you can’t put marijuana or all of Pops’ girlfriends in a book for young people, but other than that, you’ve totally captured the man I knew. I had tears in my eyes on almost every page. Reading this book was like spending time with my friend again. How the hell did you do this?”

And I said, “Jack, I’ve been informally interviewing YOU about Louis for the last 15 years. That’s how I did it.”

I asked Nat Hentoff a great deal of questions about Lester Young while I was writing Girl Singer, too. That dear man’s encouragement and generosity to me were unbounded. Oh, and by the way, I’m surviving this terrible time in American history by always saying that LESTER YOUNG IS MY PRESIDENT. The orange-headed, deeply dishonest, greedy, emotionally ill, deeply stupid bigot is not my president.

– Nat Hentoff is your admirer… That is something to be proud! How do you feel about it? How did he find your wonderful books?

-To meet Nat Hentoff was one of the joys of my life. To have Nat write two columns about me and my work is one of the true honors of my life.

It’s funny how Nat figures in my life long before I met him. When I was 13 I became a HUGE Bob Dylan fan, and the first album I took out of the library was The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan–with liner notes by someone named Nat Hentoff. Then at 15, when I decided to begin my Jazz education, I realized that Hentoff is the master of Jazz nonfiction books, too. And then at 20, when I was taking journalism courses on the First Amendment, the class was reading books and articles by Nat Hentoff on the First Amendment! So I’m thinking to myself, “This guy knows everything!”

In 1999 I finished an early version of Riding on Duke’s Train—and I have no idea where to send it. At the time, Nat was writing a column for JazzTimes magazine, so I send a copy of the manuscript to him at the magazine’s address. I’m 99 percent sure that I’ll never hear a reply.

Then a few weeks later my wife and I return from seeing a play in Boston, and the babysitter says, “A man named Matt Hentoss called and here’s his phone number. He says to call him tomorrow.” I’m thinking “Is it Nat Hentoff?” and because the area code was New York City’s 212, I barely slept that night. So of course it is Nat and the first thing he says to me is: “Did you know Duke Ellington?” I reply, “No, I was 15 when Duke died.” He replies, “Because I knew him for over 25 years. Duke was my mentor. And the Duke in your book is the man I knew. How did you do this?” (Ha! The same words I heard from Jack Bradley!) And that’s how I met Nat Hentoff. A few months later I went to New York and met him at his apartment in Greenwich Village. That man could not have been more welcoming, more generous to my work. I loved him.

To have your writing idol truly enjoy and admire your own work is something out of a daydream—but that’s what happened. I’m a truly lucky guy.

– What characteristics do you consider that a jazz writer and a jazz critic should have to be professionals?

-In order to write about Jazz musicians, I feel that one must first realize that these were not gods from Mount Olympus (although musically they were!); these were flesh and blood human beings with their own quirks and foibles. But not only that: These were human beings who were treated like dogs and trash in their own country. Men and women who could not live where they wanted to live—could not eat where they wanted to eat—could not sleep where they wanted to sleep. Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong and Charles Mingus and John Coltrane and Billie Holiday and Charlie Parker and Ella Fitzgerald and dozens of other glorious musicians could never forget in their own nation, not even for a day, about the color of their skin. Bigots would not allow them to forget. The fact that they created exalted art while dealing with this evil is beyond inspiring.

We all admire Roy Eldridge, one of the true trumpet masters. We can picture him all cocky, strutting into jam sessions in the 30s and 40s and taking on all challengers. But read his interviews. On so many occasions Roy Eldridge was brought to tears by the way he was treated by ignorant bigots not worthy to even breathe in his presence. It breaks your heart.

-It’s very important that now your novels are part of the public education in the US. I know why this is relevant, but I want to know your perspective about it.

-As my novels are adopted into more and more school systems—now several in Europe as well—I receive more and more letters from readers. Young people like to tell you about their interests, but then they get to the point of the matter: “Since reading your book or books, I’m now listening to Jazz and I love this music.” Obviously the letters are all expressed differently, but when the young people tell me that my books have opened up their minds and ears to Jazz, that’s music to my ears—because that is the reason why I began writing them: to turn on a new generation to the “glories and stories of our music,” as Nat put it. At times I’ve been frustrated that Downbeat has not published a word about my books. (And Brian Morton wrote a wonderful article on the novels in the British magazine Jazz Journal). It incensed Nat. “Don’t they understand that your books are creating future Downbeat readers?” he once said to me. But what the heck. The novels are reaching the young people through their schools, and that’s what’s important.

-The book on Duke Ellington is now going to the big screen. Tell me about this project.

-Ken Kimmelman, a New York City filmmaker who has won two Emmys, read Riding on Duke’s Train and immediately loved it. He was hipped to the novel by Ed Green, a composer and Ellington scholar. Ken said to me on the phone: “I’m very moved by this story and I think it will make a superb feature-length animated film.” Ken then asked me to adopt the novel into a screenplay and I did. I wrote the dialogue and some of the stage directions, with Ken adding some additional stage directions and all of the film terms. He’s in the process of raising the necessary funds to make the film of his dreams and he’s getting there. Not to brag, but our screenplay has won awards at film festivals all over the world. For example, it won first place for best screenplay at the 2016 International Harlem Film Festival, where a scene was presented by actors on the festival’s last night. That was a true thrill! And the 26th annual International Duke Ellington Study Group Conference will be held in March 2020 in Washington, D.C., and the noted Ellington scholar Marilyn Lester is presenting a talk on Riding on Duke’s Train—both the impact of the novel and the film’s journey. She is an exceptional writer and person and I am beyond honored that Ms. Lester has chosen this topic for her talk.

-If there is anything you would like to add, be my guest!

-Final thoughts: As a teacher of teens—I teach literature and writing—I have always played Jazz in my classrooms, trying to open young people’s ears to this incredible music. Yet it dawned on me that I was only reaching my 100 students a year. Then I thought that if I could combine real historical musical figures with fictional young people that I might be on to something. The success that my books have enjoyed has been sweet—because without new generations listening to Jazz, the music’s impact will fade away. The fact that I’m making my little contribution—along with many dedicated music teachers and musicians—is something of which I’m very proud. To put it in dear Jack Bradley’s words: “You’re helping to spread the gospel, man!”. And so are you, dear Estefania!

It is a great honor for me to share these words with you, my good friend Mick. I understand when you say how lucky you feel because your idol acclaims your work, because that is how I feel when I read your kind words on Bop Spots. Let’s keep on spreading the gospel!