By: Estefanía Romero

I invite you to read the other parts of this article: · Women in Jazz | First Part: The Notion of Inferiority · Women in Jazz | Second Part: Women who Sing Jazz (Professionally?), Attraction and Persistence · Women in Jazz | Third Part: Mexican Jazz Females |

Women in Jazz | Second Part: Women who Sing Jazz (Professionally?), Attraction and Persistence

Rejectment to Female Jazz Singers (or to the Unprofessional Ones?)

Lara Pelleginelli wrote that: “Women in jazz have traditionally been singers, a role that allows them to be dismissed as entertainers who are not fundamental to jazz as “serious” art” (et al, 2021).

Whereas it is certain that a stigma on female singers persists until this day, when I see this reality on my own times and country, I ask myself if this could actually have any fundament on the possible reality that singers just do not prepare enough… so, could that be the case? And, if so, why does that happen?

In 1939, Down Beat published another controversial opinion, this time focusing on singers: “The Gal Yippers Have No Place in Our Jazz Bands”, by Ted Toll (1939), who criticized, among other things, that the girl singers sex appeal, or the fact that the band leader is gone on her, and their beauty, are reasons to have a girl in a band, as much as this reality is being admitted by many people (or “diehards”, as Toll calls them). “But nobody seems to have bothered to find out why none of these gals (with the few exceptions, of course) can sing a song that won’t reach react like a monkey-wrench thrown into a smooth-working piece of machinery” (Toll, 1939, in Walser, 1999, p. 114.).

Another point claimed by Toll was the importance of the social context:

[…] mostly from the better negro musicians themselves, comes our best swing music today.

American’s girls have not had the opportunity to surround themselves with this environment. They’ve been tending to their knitting preparing themselves either for the kitchen or the career. Grant that those who have been preparing for the career of swing Singer have tried to learn from those predecessors who were considered best. (p. 115)

This comment announces two important subjects: 1. The relation between women (I guess he is implying only white women) and African American musicians; and 2. The fact that many female jazz singers opted for copying the best singers. In what comes to the first point, Toll is ignoring all the difficulties that white women had to face to stablish any kind of relationship with an African American person. Sheila Jordan, recognized by many as “the last great jazz Singer alive”, spoke to me about this in an interview (Romero, 2020):

E: How was being white (we must remember that Sheila is actually Native) in a culture of black people’s music… and being a woman?

S: It was very difficult being white because Detroit was very prejudiced, they would not like black people, especially a young white girl singing with African American kids, so I had a hard time, but I never thought about color. You know? I didn’t have that kind of thing growing up because of having been prejudiced against myself for being native… you know?

I never think about it, but it was difficult in Detroit, the white people were very prejudiced and the cops, the policeman were very prejudiced, and they would constantly stalk me and take me to the police station for being with my friends, who happened to be African Americans. They were just my friends, I didn’t know… color, yellow, red, orange? black? white? I don’t know, they are my friends, I don’t think about it.

E: I am sorry to hear that.

S: Well, that’s the way it was then, it’s kind of getting better but still not great. But, you know? I stuck in there, most kids wouldn’t keep it up, they would have said “I can’t go through with this”, but the music was too important to me and I wanted to be around this music and in order to be around it I had to be in a culture that wasn’t accepted in Detroit, Michigan, or in the United States for that matter, there was all that hatred for Afro Americans, especially if you were white and you wanted to be with your friends.

It was so difficult, but I never gave up because I loved my friends and I loved the music so much, so I decided “that’s their problem… if they want to be prejudiced, I’m gonna keep it going even if I have to stick up for them or be chasing down to the police station and be questioned for being with my friends who happened to be Afro Americans”. It was difficult, but I stuck in there and I’m glad I did.

In what comes about Toll’s second point, I must add that, after having written many reviews, I’ve noticed that many women who call themselves “jazz singers” (of course, I’ve heard mostly Mexicans, but I won’t deny I’ve found this in women from other nationalities) tend to copy the great jazz singers, thus erasing the possibility of having a voice of their own. As Billie Holiday said once:

Everyone’s got to be different. You can’t copy anybody and end up with anything. If you copy, it means you’re working without any real feeling. And without feeling, whatever you do amounts to nothing.

Not two people on earth are alike and it’s got to be that way in music or it isn’t music (Holiday quoted on Ritz, 2006, p. 52).

According to the Chaikin’s documentary (2013), women were always rejected from orchestras and jazz ensembles… but, let’s remember that Artie Shaw accepted Billie Holiday in his band, knowing that no one else (man or women) could sing that way.

To Toll, many singers are “victims of a heritage of classic yoddeling” (p. 115). I’d like to add to this point something that Aaron Copland explained around those years (in 1936), and it’s the fact that since Haendel’s opera there has been a great preeminence of singers, above the instruments:

In this type of opera […] all the interest is centered on the singer and the vocal part, and the opera is only justified by its musical appealing. This evolution ended up being very dangerous, because very short in time the natural desire of singers to become the center of the attention led them up to commit serious abuses that still haven’t been able to be completely extirpated from music. Rivalry amongst singers led them to add all kinds of trillings and flippery to the melodic line, with the only purpose of exhibiting the great feats of the performer[1] (Copland, 1986, p. 171).

This hasn’t changed in popular music indeed. Toll (1939) said that the “yoddeling”, plus the intent to sing emotional blues, went into the creation of popular singers of something that is not jazz. Also, we can see the raising audiences in jazz concerts that applaud the singer who “feels deeply”, above the musical role that they should actually be performing.

The problem is, and Walser (1999) insists on it, that “not everyone who feels deeply sings well” (p. 115) –you can always check on Florence Foster Jenkins to take a closer view into this point– and, certainly, not everyone who sings can be a jazz singer.

To Hire Women as a Visual Attraction

Peggy Gilbert, band leader and sax player, answered back (also in Down Beat) to the anonymous article from 1938, with a speech that also works as a refute to Ted Toll, because she indicates similar arguments on environment and education (Walser, 1999, p. 116).

Gilbert wrote: “She could be good, but no matter how good, the public, especially the men, would not tolerate an unattractive, second-hand stage prop. […] For women, as a profession it can last at best only a few years” (p. 116).

Gilbert continued her battle by saying:

Your weak, illogical, ineffectual argument is hardly resented. It’s your attitude we resent, because it expresses the attitude of all professional men musicians toward all professional women musicians. A woman has to be a thousand times more talented, has to have a thousand times more initiative even to be recognized as the peer of the least successful man. Why? Because of that age-old prejudice against women, that time-worn idea that women are the weaker sex, that women are innately inferior to men.

So you actually think that because men have centuries of musical education behind them that the present masculine generation has inherited that knowledge, that talent? That’s not worthy of you, Father. We expect better arguments than that. Knowledge is not hereditary (p. 116)

Gilbert was wise to attack the tendency of hiring women as an attraction, which leads for the managers to be continuously reminding girls that they shouldn’t take music seriously, but to relax and smile. “How can you smile with a horn in your mouth” (Gilbert in Walser, 1999, p. 117). The sax player added that “Men have always refused to work with girls, thus not giving them the opportunity to prove their equality. This is especially true of wind instrument players” (p. 117); she said that if that women inferiority could be proven by their lack of practice, then the reason of it is that women do not have a future in this career because of all the previous reasons she mentioned.

All of this seemed to dress up the other part of the critic published in Down Beat: “in these show bands [the author means big bands], the prime requisite [for a girl to be in] is good looks” (Anonymous, 1938, quoted in Walser, 1999, p. 113).

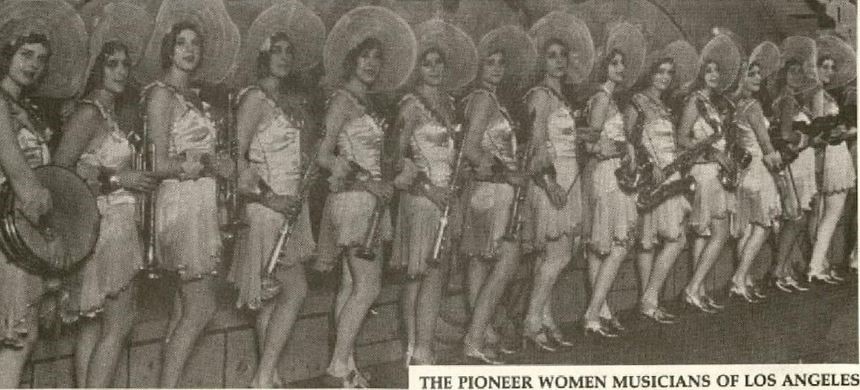

To build on this matter, let’s remember the documentary The Girls in the Band (Chaikin, 2013), which highlights intense affirmations about the 30’s and 40’s, such as:

“If Mary Lou Williams had been a man, she would have been able to do so much more for the music, for herself” (Bill Taylor, composer); “You had to have girls who think more about how they look than how they played”, or “the guys could have white hair and glasses and weight 300 pounds, but if they can play, great! The girls had to sing like a bunch of young starters”.

Funny fact: a long time ago a guitar female jazz player told me: Estefanía, you’re a great writer, but if you were a fat 70-year-old man, then people would listen to you”. I am still wondering if that could be true.

A case that I always find fascinating has been Anita O’Day. Healey (2016) quotes her, when the singer spoke on wearing a jacket like the rest of the musicians on her band, instead of the classic dresses and feminine outfits: “[I wanted audiences to] listen to me, not look at me. I wanted to be treated like another musician, not a trinket to decorate the bandstands… [but soon rumors circulated] that I preferred ladies to men!”.

A female interviewed by Healey reckons that women have to work harder than men. Another woman interviewed by Healey remarked that she wanted to be “like one of the guys” when they are with the other members of their band, which suggests, as Healey reflected, that even today the feminine identity and equality in jazz ensembles seem incompatible.

To all of this, I wanted to add a view that people tend to forget: the biological one. The neuroscientist and musical producer Daniel J. Levitin explained a psycho-social characteristic that might be useful to understand al extra element (from gender) that also impacts people’s professional development: the physical (genetical) aspect, which influences the way others behave toward a person. As Levitin put it:

The world generally reacts towards an organism in a determined way, considering its appearance. This intuitive notion has a rich tradition in the literature, from Cirano de Bergerac and Shrek: both rejected by people who feel revulsion towards how they look, they rarely have the chance to show their inner self and their authentic nature […] This also operates inversely: people with good appearance tend to gain more money, to get better jobs, to get better works and to declare they are happier. Even independently from the fact of one considering himself/herself attractive or not, their appearance influences how we relate to that person. Someone who was born with facial features that we relate to trustworthiness (big eyes, for example, arched eyebrows) is someone whom people will tend to trust on. It is possible that we show more respect to a tall person than to a shorter one. Many of the incidents that happen in our lives are related in certain measure to how people see us. (2019, p. 217)[2]

Considering this, it is easy inferable that the musical projects which are looking for a good deal in the music business, instead of proposing and showing deep artistic aspirations, seem to pay good attention to the looks of the person they put in the front of the band. This is pretty obvious for both genders. If not, what would be the point of creating boy bands? Why using Paco de María (a lame Mexican singer) instead of others (or non) in front of the jazz bands? A few years ago, I listened in a press conference with Il Divo, how journalists couldn’t stop asking questions to the singers about their favorite beauty products. Without getting too deep into this topic right now, this is something I propose to corroborate in future comparative studies.

Why being part of the jazz world and persist… or just leave it?

Aimee Nolte (2019) quoted the book Reviving Ophelia, by Mary Pipher, when she said that teenage women, looking for acceptance, start to pretend certain things and leave behind what they love. Nolte’s intention is to invite young women to the music’s world and help them to grow on it. When I saw this, in my mind appeared multiple examples, one of them was Beyonce thanking Tina Turner publicly for being an inspiration as an African American woman who can go far in music.

According to Healey (2016), many researchers agree on how the absence of role models negatively affects the successful expectations in a given field:

A 2012/13 report found that across all music industry jobs, 67.8% were filled by men, compared with 32.2% women. A 2001 review of active members conducted by a United States music educators’ organization found that in 2001 only 23% of its members who were jazz teachers were women. A 2015 Music Victoria discussion paper on women in the contemporary music industry in Victoria, Australia, found pay inequality, sexual harassment, and poor working conditions were common issues reported by women.

In her own research, Healey asked a few women if representation would help to improve the role of women in jazz, to what they answered: “it had to be merit based”.

Some of the females I interviewed agreed to Nolte’s hypothesis on representation, although I, personally, agree to it just to a certain point, because I think reality can be more complex than that. I come from a middle-class Mexican family, I still haven’t found the example of a woman dedicated to write jazz criticism, but I do dedicate my life to it. However, this might respond to individual characteristics from my own environment that led me to create my own lifelong project (maybe no one told me I couldn’t do something for being a woman). I also wonder, how could Nolte explain, let’s say… Stevie Wonder being Lady Gaga’s role model on music? Or Oscar Peterson and Errol Garner being Hiromi Uehara’s main figures of inspiration at her beginnings? Moreover, how could Nolte justify, under her vision, the real professional motors behind Nina Simone or Ella Fitzgerald? We know their stories and we understand that there is always more than just one simple explanation; anyway, I couldn’t completely take away the credit on the idea that creating inspiring figures is always important. To see more women prepared on jazz would sure motivate ladies from the next generations to be part of it.

You may continue the reading of this article: · Women in Jazz | First Part: The Notion of Inferiority · Women in Jazz | Third Part: Mexican Jazz Females |

[1] The source from where I took this information was already a translation in Spanish, so I had to “retranslate” the quote in English, trying to make it the most literal possible for the reader to catch Copland’s speech.

[2] This is a translation I made from the Spanish version of this book.